An important aspect of effective threat hunting is to understand what is normal in an environment. If a threat hunter is able to baseline the normal behaviour in a system then any abnormality is most likely due to an actor that has newly entered the environment. This actor could be a new software installation, new user or an attacker.

On endpoints, the execution of certain Windows processes is well documented. If we can map out the normal execution behaviour of these processes then we can easily flag execution of similar looking – but abnormal – processes on the systems. To confuse incident responders and analysts, attackers nowadays resort to the use of executables with similar names as the system processes. So, a cursory glance by the user or investigator may not identify a malicious piece of binary on the system. This technique which is popular among APT and malware groups like APT1, Carbanak, Elise etc. is called as ‘Masquerading’.

In this post, we shall look at behaviour patterns and features of some Windows system processes and how we can embed that knowledge into a ‘rule’ to then identify any process which does not conform to the rule.

We shall use below components to conduct the hunt:

- Sysmon: This Sysinternals tool is an excellent windows event logger. It can generate detailed logs of process execution events on a Windows system.

- Winlogbeat: This is a log shipper of Windows events. It is part of the Elastic stack.

- ELK stack: The analytics and visualization platform. This framework will be used as our ‘Threat Hunting’ platform. Logs generated on Windows systems by Sysmon will be shipped to ELK stack by the winlogbeat shipper.

For this blogpost, we will not cover ‘Windows Processes internals’ in depth, but if this post makes you curious about it, we would recommend reading the excellent Windows Internals Part 1 and Part 2 by Mark Russinovich, who is also the author of Sysmon and the larger sysinternals toolkit.

Let us take an example of the smss.exe process on Windows. This service refers to ‘Session Manager’ and has the following characteristics

- It is the first user mode process.

- The parent process must be System

- It loads from %systemroot%\System32\smss.exe

- Username should be: NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM

- It creates two sessions: Session 0 – OS services and Session 1 – User Session

- Session 1 will exit after loading csrss.exe and winlogon.exe. (Hence, these two processes will not have a parent process)

- Only one smss.exe with session 0 should be running. (If there are more than one instances running, that means either it is fake or more than one user is logged on to that system).

Many of these details can be checked with the Sysinternals Procexp.exe utility.

Now that we know how a genuine Windows smss.exe process looks like, we can use this information to hunt for any other smss.exe process in the entire infrastructure which does not match these features. In our case, we are specifically hunting malicious processes which are masquerading as a genuine process. A common technique to identify such binaries is to look at their parent process name and their path of execution. A list of standard Windows processes along with their parent process and execution path is provided below for reference. You can refer to the SANS Find Evil Poster for more details.

| # | Image Name | Image Directory | ParentImage |

| 1 | svchost.exe | C:\Windows\System32\ | C:\Windows\System32\services.exe |

| 2 | smss.exe | %Systemroot%\System32\ | System |

| 3 | csrss.exe | %SystemRoot%\system32\ | – |

| 4 | wininit.exe | %SystemRoot%\system32\ | – |

| 5 | services.exe | %SystemRoot%\System32\ | %SystemRoot%\System32\wininit.exe |

| 6 | lsass.exe | %SystemRoot%\System32\ | %SystemRoot%\System32\wininit.exe |

| 7 | svchost.exe | %SystemRoot%\System32\ | %SystemRoot%\System32\services.exe |

| 8 | lsm.exe | %SystemRoot%\System32\ | %SystemRoot%\System32\wininit.exe |

| 9 | winlogon.exe | %SystemRoot%\System32\ | – |

| 10 | explorer.exe | %SystemRoot%\ | – |

| 11 | taskhost.exe | %SystemRoot%\System32\ | %SystemRoot%\System32\wininit.exe |

Table 1Windows Processes

Sysmon can be used to generate the full process execution logs. Below is the list of log events generated by Sysmon.

| Event IDs | Event Class |

| 1 | Process Create |

| 2 | Process Terminate |

| 6 | Drive Load |

| 7 | Image Load |

| 2 | File Creation Time Changed |

| 3 | Network Connection |

| 8 | CreateRemoteThread |

| 9 | RawAccessRead |

Table 2 Sysmon Event IDs

We will be focusing on Event ID 1 which is generated on every new process creation. We will get these logs into ELK via Winlogbeats.

Logstash can be used to analyse and tag events which do not match the above rule pattern. Taking the example of SVCHOST.EXE, we note that its parent process name is “SERVICES.EXE” and it is executed from the System32 directory. This can be defined as a ‘rule’ in logstash as shown below.

if “svchost.exe” in [event_data][Image] and ([event_data][CurrentDirectory] !~

/(?i)C:\\Windows\\System32\\$/ or [event_data][ParentImage] !~

/(?i)C:\\Windows\\system32\\services.exe$/) {

mutate {

add_tag => [“suspicious process found”]

}

}

Whenever we come across a process with the name svchost.exe which is not executed from the C:\Windows\System32\ directory or which does not have a parent process called services.exe (which itself was launched from C:\Windows\System32\ directory), then a tag is added to the event for further review and investigation.

Note: The “C:\” is hard coded with the assumption that majority systems have Windows OS installed on C drive

If you are unaware of the logstash configuration file syntax, you can refer to these articles:

https://www.elastic.co/guide/en/logstash/current/configuration-file-structure.html

https://www.elastic.co/guide/en/logstash/current/event-dependent-configuration.html

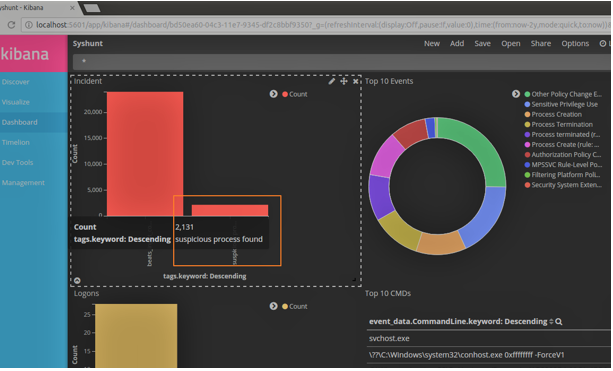

We can create similar rules for other system processes as well. A simple metric count visualization can now be created for this tag (suspicious process found). Anytime the count increase, we know there’s something funny going on in the infrastructure.

Figure 1: Tags: suspicious process found in Kibana

Figure 1: Tags: suspicious process found in Kibana

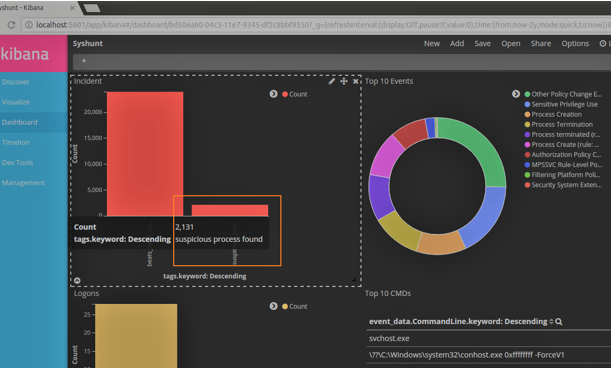

Figure 2: Co-relating found suspicious process

Figure 2: Co-relating found suspicious process

In subsequent posts, we will explore setting up and configuring Sysmon and ELK to provide a complete threat hunting cycle. Till then Happy Hunting!